[Shortcut down to the rest of the article]

by Vikki Conwell and Shelia M. Poole

When Gordon Williams began working for a glass container maker some 30 years ago, the work was fast and hard. Today, he says, it's even faster and harder. The number of workers has gone down, while job demands have gone up, says Williams.

"There is just no way people can keep up with the expectations they [employers] have," said Williams, 59, of Atlanta. "It's definitely lean, but it's also mean."

Williams is among millions of U.S. workers who, over the past few years, have discovered that in today's workplace, leaner and meaner can actually be just that---and there's little they can do about it. "It hurts financially and emotionally, because you worry so much," says Williams.

In the long run, companies will suffer, too, experts say, on the bottom line as they pay the price later for what some are doing to their workers now.

Budget-cutting is rampant and wages are stagnant, observe Lesley Wright and Marti Smye, authors of the book "Corporate Abuse: How Lean and Mean Robs People and Profits" (MacMillian). Wright, a marketing and advertising creative consultant, spent 22 years working as an advertising executive for a number of agencies. Smye heads a firm that specializes in planning and implementing large-scale organizational changes. Her clients have included multinational and Fortune 500 corporations.

"In this atmosphere, individuals are sacrificed for the sake of the bottom line," they write. "Overworked, bullied and micromanaged, we find our contributions rarely acknowledged, our ideas passed over, and our time and energy spent more on office politics and power games than on efforts to get the job done. In short, we are being abused."

The underlying facts are harsh: From June 1995 to June 1996, job cuts were made by 49 percent of major U.S. companies, according to a survey by the American Management Association. That's despite a growing economy that will see corporate profits top $760 billion this year.

And wages and benefits, which have risen 2.8 percent since 1989, adjusted for inflation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, are not keeping pace with productivity.

In short, while the economy is booming, worker gains are down. Some analysts believe the national strike of 185,000 Teamsters against Sandy Springs-based United Parcel Service partly reflects those seemingly contradictory economic circumstances. Among the Teamsters' issues: the company's growing use of part-time workers, which make up about 60 percent of UPS jobs.

Across metro Atlanta, workers are complaining about their work life. Dozens of callers to a Journal-Constitution hotline on the workplace complained of overwork and fewer benefits, discrimination, arbitrary dismissals, penny-pinching and micromanagement.

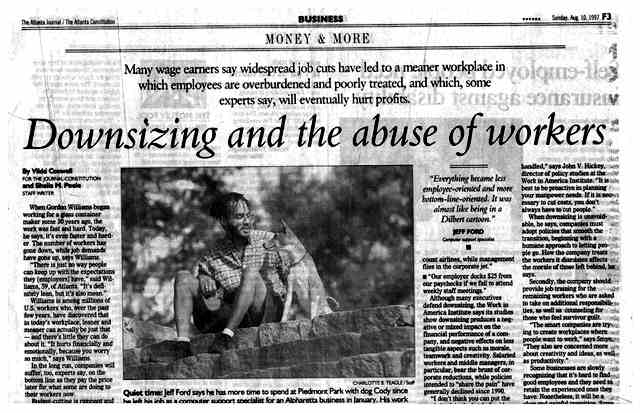

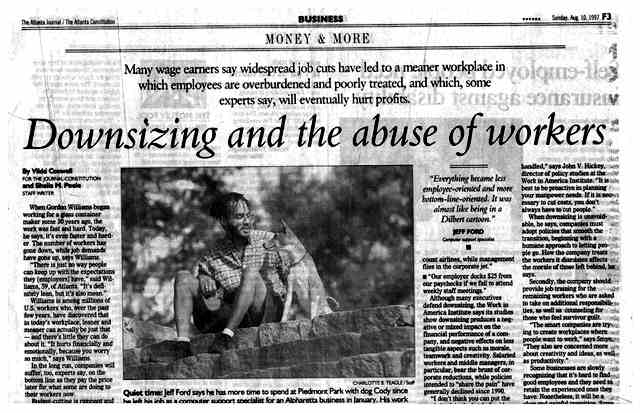

Atlantan Jeff Ford watched the workload at his Alpharetta-based employer grow, while the number of workers in his work group fell from 18 to three.

"They were never replaced," said Ford, who finally left the company in January and now plans to open his own business.

"Everything became less employee-oriented and more bottom-line oriented. It was almost like being in a Dilbert cartoon. Everyone is trying to do more with less," he said.

Here's what some other callers had to say:

Although many executives defend downsizing, the Work in America Institute says its studies show downsizing produces a negative or mixed impact on the financial performance of a company, and negative effects on less tangible aspects such as morale, teamwork and creativity. Salaried workers and middle managers, in particular, bear the brunt of corporate reductions, while policies intended to "share the pain" have generally declined since 1990.

"I don't think you can put the genie back in the bottle," said Rick Cobb, vice president of Challenger, Gray and Christmas, an executive outplacement firm in Chicago. "Companies will not admit that they have reduced their staffs by too much, that they need to staff back up and the remaining workers are overworked."

In the long run, however, it may not pay for companies to push workers to the edge, says Tucker consultant Terry I. Wynne, owner of the Professional Edge.

"People have to work so many hours of overtime that their bodies are wearing out, and they are getting sick. I hope the pendulum will swing from trying to do more with less to letting people have a more balanced lifestyle."

Stress, headaches, ulcers, exhaustion, insomnia, anxiety, burnout, heart attacks, panic attacks, nervous breakdowns---all have been traced to working environments that breed fear and hostility, Wright and Smye observe in their book. They point to studies that estimate the business cost of burned-out, dispirited employees at between $150 billion and $180 billion per year.

There's a lesson for companies to learn, experts say.

"The worst thing a company can do is simply set a numerical goal and cut people without any regard to how the work will be handled," says John V. Hickey, director of policy studies at the Work in America Institute. "It is best to be proactive in planning your manpower needs. If it is necessary to cut costs, you don't always have to cut people."

When downsizing is unavoidable, he says, companies must adopt policies that smooth the transition, beginning with a humane approach to letting people go. How the company treats the workers it dismisses affects the morale of those left behind, he says.

Secondly, the company should provide job training for the remaining workers who are asked to take on additional responsibilities, as well as counseling for those who feel survivor guilt.

"The smart companies are trying to create workplaces where people want to work," says Smye. "They also are concerned more about creativity and ideas, as well as productivity."

Some businesses are slowly recognizing that it's hard to find good employees and they need to retain the experienced ones they have. Nonetheless, it will be a slow and painful transition, Smye says.

"Too many people will suffer too much because not enough leadership

will take over to find a solution fast enough."

Help Yourself

What most people feel in the current work environment is a lack of control, says Marti Smye, co-author of "Corporate Abuse: How Lean and Mean Robs People and Profits." Here is what she suggests to help add some measure of control to your work life: